Jobs to be Done or everything you need to know about your users’ desires

Imagine selling a camera that immediately processes and prints photographs. You know that your customer is Nancy; she is 27 years old, studying at the Institute of Culture and is an active Instagram user. You have a quite detailed description of the person on your hands, but which of these facts influenced the purchase of the camera? None. But you were selling this camera to nearly everyone who looked like Nancy. And what if sales started to fall or you decided to create a new product? How, in this case, can we understand who your target audience is and why they should buy from you? The solution lies in the theory of Jobs to be Done.

Jobs to be Done — what’s it all about?

Jobs to be Done is a theory about user behavior that helps understand how and why people make their first purchase decisions. With JTBD, we can make forecasts about which product will be in demand in the market and which will not.

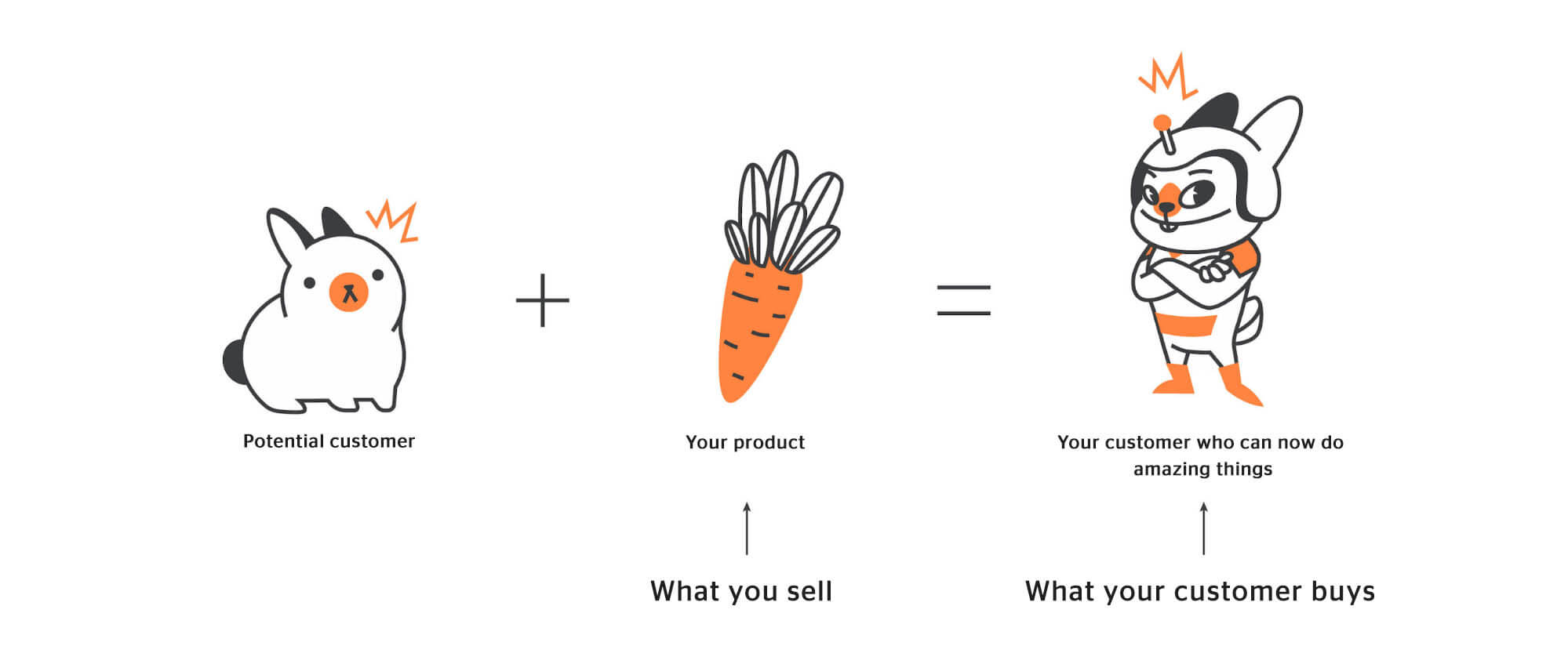

The meaning of the theory is that people do not buy products, but “hire” them to perform certain tasks.

I’m not buying a lawnmower because I need a lawnmower. I need a beautiful lawn, and more broadly, a beautiful yard so that all my neighbors go into the rant as they pass by my garden.

The theory of “jobs” suggests that the global goal of each person is to become better, and the product should help in this.

This approach is different from customer development or the concept of user personas. Instead of creating a collective image of the target audience and finding out how the user utilizes the product, the “jobs” theory helps explore user insights and challenges.

No matter how people use the products, it’s important why they bought them. Every person experiences a Struggle Moment before buying any product. The concept of JTBD helps us find out what the moment was. At the same time, the theory does not exclude the use of other research methods. The audience data can be combined with JTBD and become even more useful. After all, you will know not only who your potential customers are, but also why they buy from you.

With the help of the “Jobs” theory, we can learn what drives people when they make a purchase decision, which means we have the ability to create products that will better respond to internal customer requests.

The goal of JTBD is to understand why users have bought products in the past and predict whether they will buy them in the future.

Why do we need Jobs to be Done?

Roughly speaking, the theory of “jobs” helps you get as close as possible to the true desires of the user and create products based on these desires that are more likely to be in demand in the market.

You need to explore JTBD if you want to:

- understand why users have bought your products in the past;

- forecast what products users will buy in the future;

- define unobvious competitors;

- understand how the decision-making system is organized;

- learn to analyze data correctly;

- gather data and draw the right conclusions from it;

- create innovative and demanded products;

- be competitive.

JTBD helps with product creation and its further promotion. With this theory, you can learn how to increase revenues, reduce costs, achieve competitiveness, and develop more predictable innovative products.

Who Jobs to be Done can help?

Everyone.

If you have a product or a service, you can safely begin to live by the laws of the “jobs” theory. The concept of JTBD gives an idea of why users buy and use products, which means that the theory is applicable in all areas.

The theory of “jobs” can help develop disruptive innovations. If product marketers know what “jobs” users have, then they understand what product they need.

The JTBD theory represents a change in thinking in product development and market research, on which it is based. The theory appeared when it became clear that developers and marketers needed a new paradigm regarding user value. The value should be in what the product does for the user, not in what the product is. In other words, try not to associate the value with the new features and start developing more complex products that will be valuable because they do a certain job for which the user has hired them.

Read also:

👉 Live Chat Best Practices: 20 Hacks to Make Customer Service Better

👉7 Best Live Chat for eCommerce: Boost Conversion on your Website

👉 Top 5 live chat mobile app: find the best fit for your business

👉 Live Chat: How Online Chat Tool Can Help Your Business

👉 20 Best Live Chat Software for your website chat service

👉 Acquisition funnel marketing: Grow customer conversions at each step of user journey

👉 The top 15 inbound marketing tools: harness digital power and elevate your business

👉 10 best website personalization tools to deliver top-notch visitors experience

👉 7 best email capture tools: features and pricing compared for 2024

Two interpretations of Jobs to be Done — dotting the I’s

There are two interpretations of JTBD and they have fundamentally different views on the definition of a “job”. If you really want to connect your life with JTBD, you should know which of the successors to worship?

Two versions of Jobs to be Done:

- Jobs-As-Progress: The theory was developed by Clayton Christensen, Bob Moesta, Alan Klement, et al.

- Jobs-As-Activities: The theory was developed by Anthony Ulwick.

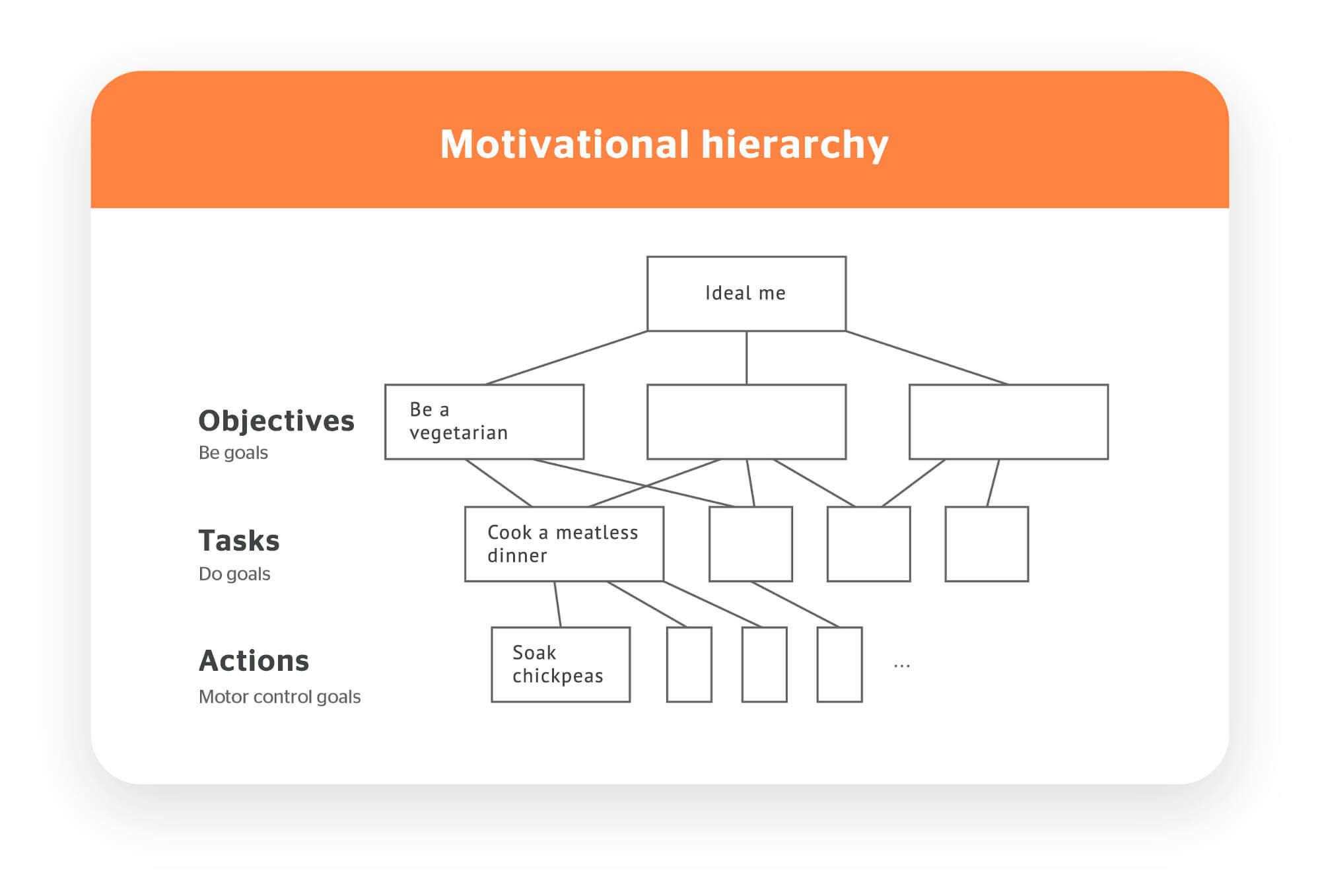

But before we proceed with the interpretation, let’s look at the diagram below.

This diagram shows the motivational hierarchy of William T. Powers, an author of the perceptive control theory that defines the relationship between what we strive for and what we need to do. That is if I want to be a vegetarian because I’m an animal right and environmental activist, I have to cook a vegetarian dinner, and for that, I have to soak chickpeas for 10 entire hours! In this hierarchy, “Be a vegetarian” will be my major objective and a Be goal; “Cooking a vegetarian dinner” will be my Do goal, and “Soak chickpeas” will be my major action and that is a Motor control goal.

Now we know what types of tasks we have and what priority each of them has, but how do they affect each other and what is the relationship between them?

If I don’t soak chickpeas (come on, it takes so long!), but just clean the avocado and cut off a piece of bread, it will still count as dinner, that is, the action is not done, but the task is still achieved. And if I don’t cook dinner and go to a vegetarian restaurant, I won’t stop being a vegetarian. That is, Be goals have the highest priority and do not always depend on Do goals and Motor control goals.

Now let’s look at it from the other side: your main objective is still to be a vegetarian, the task is to go to a vegetarian restaurant, and the subtask is to take a taxi, walk to the restaurant, etc. You get in a taxi, come to a restaurant, order food, eat it, and then find out that there was pork seasoning, because you’re in China, and there is no way you go without it. You accomplished all the necessary tasks, but the big objective was not achieved.

What is the conclusion of all this? Tasks and subtasks are not as important as the main objective and do not always influence the achievement of that objective. Remember that and let’s move on to the two versions of JTBD.

Ulwick’s Jobs-As-Activities

The theory was developed by Anthony Ulwick

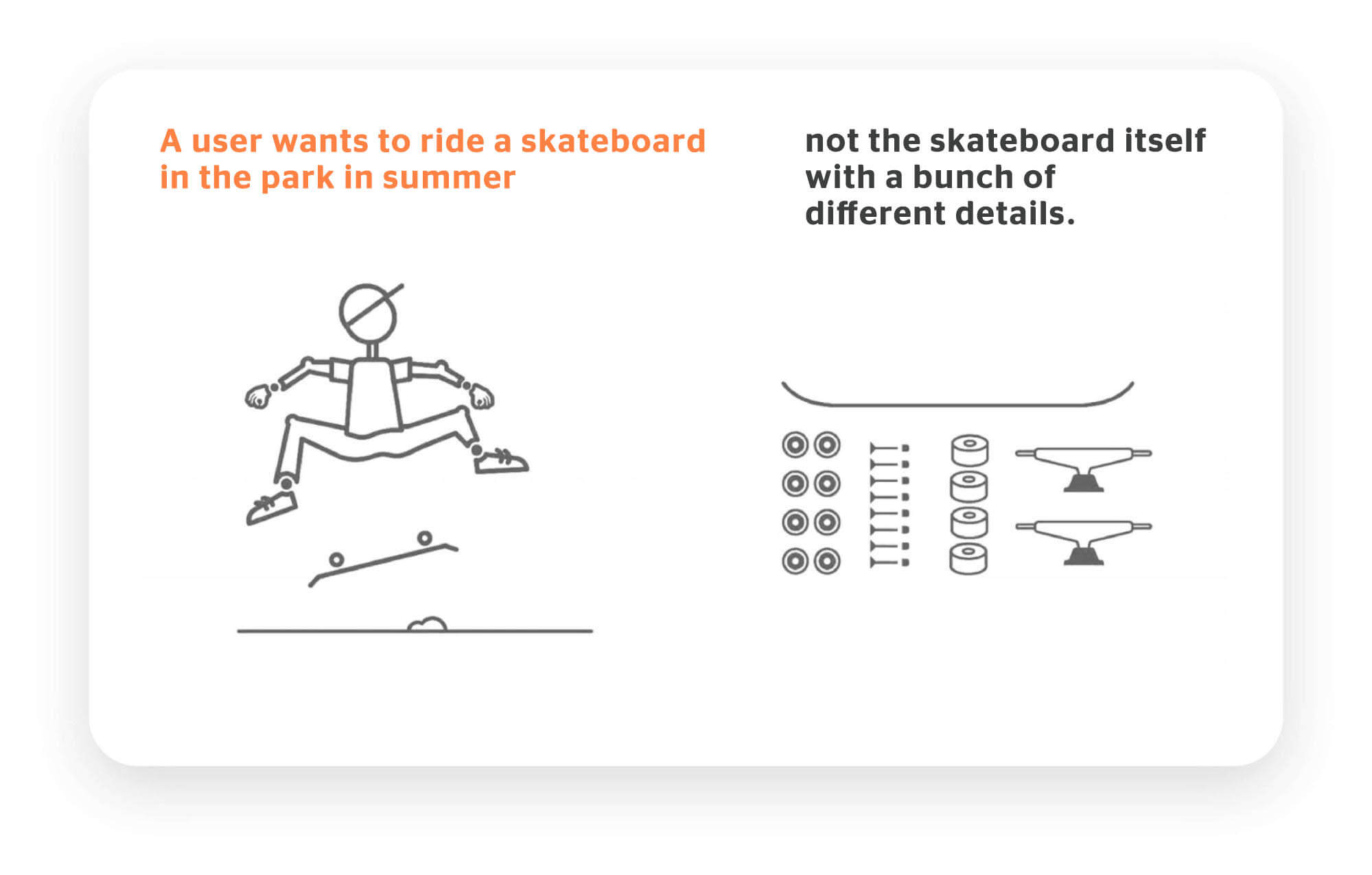

Ulwick interprets the theory in the following way: a person hires a product and the process of completing a task is important to them. I’m buying a drill to drill a hole in the wall. I’m buying a lawnmower to mow the lawn.

In his book, he defines JTBD like this: the action, task, or objective a person is trying to accomplish. The job can be functional, emotional, or associated with product use.

Ulwick’s concept assumes that users want to perform actions and tasks. He uses such examples of “jobs” as “listen to music”, “drill a hole in the wall”, “download music”, “cut down a tree”. Tasks are at the heart of the whole analysis. Any emotional considerations are secondary to a functional job:

“Emotional jobs determine how the user wants to feel as a result of performing basic functional jobs. Social jobs determine how the user wants to be perceived by others”.

In Ulwick’s interpretation, we hire a product to perform tasks with it. And now, remember the motivational hierarchy diagram. In it, tasks (Do goals) and actions (Motor control goals) have the lowest priority and do not always affect the global objective of “Becoming better”.

Christensen’s Jobs-As-Progress

The theory was developed by Clayton Christensen, Bob Moesta, Alan Klement, et al.

Everyone else (Christensen, Moesta, Clement) believes that a person hires a product in order to become better. I’m not buying a drill because I want to drill a hole or because I need a hole in the wall. I want a nice house.

Clayton Christensen is one of the first to develop JTBD, he is also the author of the disruptive innovation theory. For this reason, JTBD is very often used in solution development for disruptive innovations, as the main task of the theory is to predict the changeable desires of users.

When Apple was selling an iPod, it was breaking sales records, but the company decided to launch a new product that would later kill the player. This product was the iPhone and it really collapsed iPod sales, but that’s how Apple predicted the true need of users for one device and extended its growth.

According to Christensen, a job is the progress one wants to make to be an improved version of themselves in the future.

The Jobs-As-Progress model assumes that the user searches, buys and uses the product for the first time when there are discrepancies between how things are today and how we want them to be in the future. Job-as-progress is about the user’s desire to use the market to resolve the “Be goal” discrepancies.

The Jobs-As-Progress model helps us understand why users change their historical patterns of consumption — why they stop using one product and start using another. It is very important to try to determine what preceded this behavioral change.

So, now you know about two interpretations of the theory and you can choose which side to take. Both approaches attempt to identify what drives users when they purchase goods or services. But Jobs-As-Activities sees jobs as tasks, and the Jobs-As-Progress model sees them as progress.

We like Christensen’s interpretation more and we want to talk more about Jobs-As-Progress.

A little deeper into Jobs-As-Progress

We’re about to become familiar with Alan Klement’s model. He assembled it from the models of his colleagues and claims that it only includes the best of his predecessors’ work.

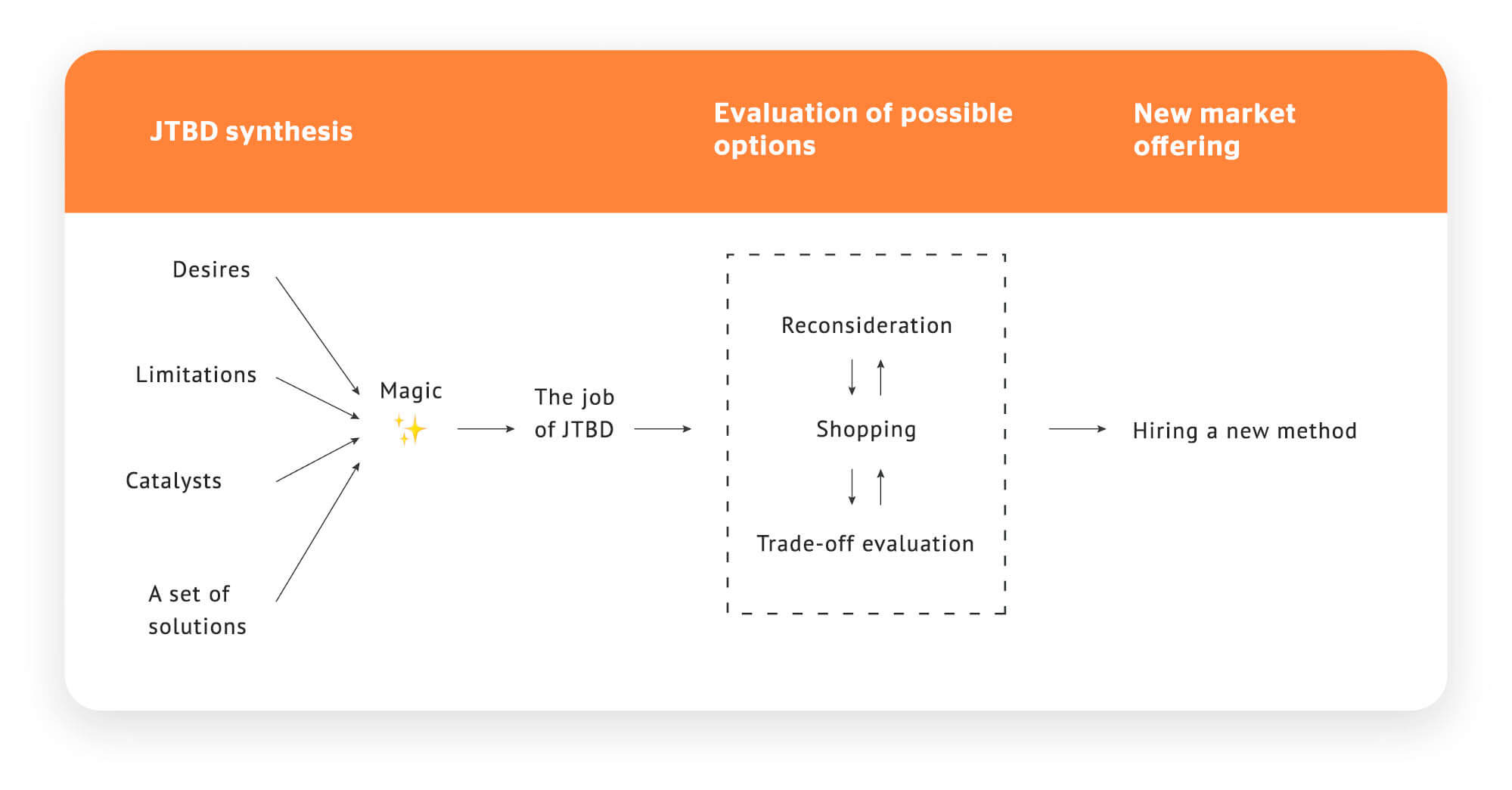

This model is designed to describe how jobs are created and how these jobs cause the hiring and firing of the product.

This model is similar to the chemical reaction: as a result of joining several elements, “magic” happens and something absolutely new is created. In our case, this is a job to be done.

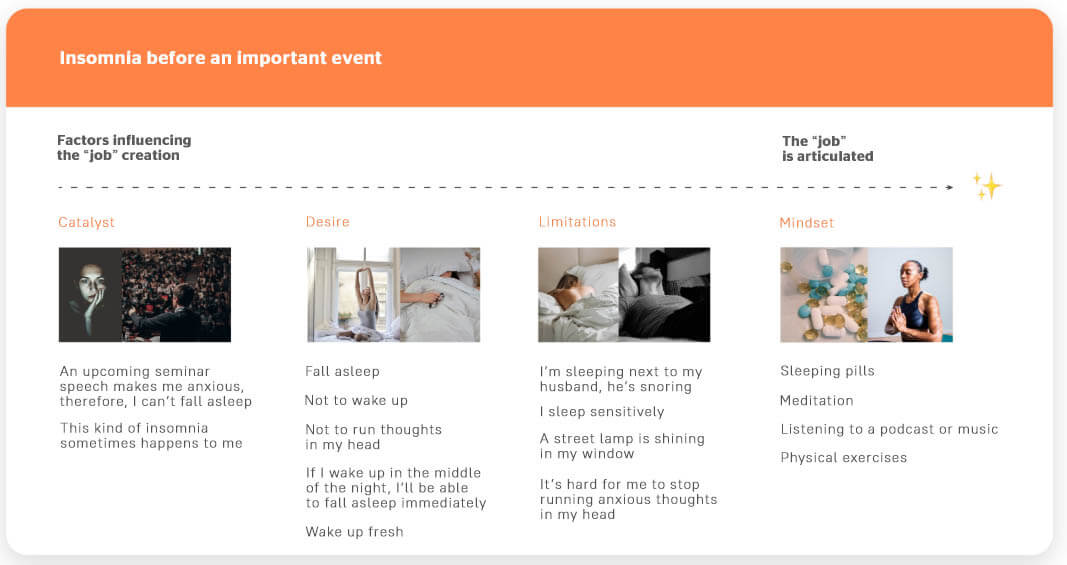

Let’s start with the first part — the JTBD synthesis. The synthesis occurs when desires, limitations, catalysts (an event that causes a desire), and a set of solutions are combined together. What does energy mean? It is the user’s mindset when they decide to leave the comfort zone and understand what they need to make progress. This is how Jobs to be Done appear.

Once the user has articulated the job, they move on to the “option evaluation” step. At this stage, it is up to the user to determine which of the options to hire:

- Shopping: a user starts gathering information looking for something and choosing the best solution for the job. Shopping can be a trial registration or just a Google search for the “best CRM”.

- Reconsideration: to become better, a user hires solutions that they’ve tried before. It’s like drinking sedative pills again to calm down and fall asleep. If during reconsideration a user fails to achieve their objective, they go shopping.

- Trade-off evaluation: a user estimates what they are willing to give up for a new solution and how much energy, money, time, effort, etc they are willing to spend.

After a long reconsideration cycle, trade-off evaluation, and shopping, we move on to the final stage of the model, which is the formation of new market behavior. At this stage, we fire the old product and hire a new one. This stage helps us understand how new markets are created, and old markets are closed.

Now you know how the decision-making cycle works, and you have the ability to measure, evaluate and predict jobs.

Sounds cool, how do I put it into practice?

Dimitrii Kapa, the co-founder of the USEFUL agency which conducts user research on the “jobs” theory, says in his interview: “JTBD is not a framework or a tool, it is primarily a theory that helps you look at how people make decisions at the right angle. It is about how people choose and continue to use a product or a service.

The theory of “jobs” does not replace any existing approaches and work processes. If your company has its own processes or you use Customer Development, Lean, HADI cycles, CJMs, they all perfectly complement the theory itself.

Since this is a theory, many JTBD advocates create frameworks and models for application based on it. We in our agency also develop frameworks sometimes, and you can come up with your own model and implement it into the company’s operation.”

Well, we know why we need JTBD, we have heard about two interpretations, we have understood what suits us best, we have seen the jobs model, and we urgently want to start learning user insights and making cool products, but how do we do that?

This was the first part of a big material on JTBD. In the second chapter, we will tell you how to apply the theory in practice.

Stay in touch!

The article was based on a free adaptation and translation of Alan Klement’s book “When coffee & kale compete?”

![Build Ideal Customer Profile Like a Pro Even If You’re Not [3 Templates]](https://www.dashly.io/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/ideal-customer-profile-4-720x308.jpg)